- Copy.jpg)

Attention: Links on this page only work if you click on them and choose "open link in new tab"

I've published two books altogether. The first is called Turks Across Empires, and was published by Oxford University Press in 2014. My second book is called Red Star over the Black Sea: Nâzım Hikmet and his Generation. It was also published by Oxford University Press, in 2023.

Additionally, a Turkish translation of Turks Across Empires came out in Turkey as İmparatorluklar Arası Türkler in 2021. A Turkish translation of Red Star over the Black Sea is due out by 2026 or so.

Red Star over the Black Sea: Nazim Hikmet and his Generation

I got the idea of writing a biography of Nâzım Hikmet when I was visiting Istanbul in 2015. I had just published my first book, Turks Across Empires, and had recently been awarded tenure and promotion to associate professor. So, I was feeling pretty good about myself at the time.

In retrospect, I think I was able to come up with a good topic for a second book precisely because I was not looking for one. Indeed, something I'd noticed about a number of my academic peers is that, in many cases, their second book ends up being more or less about the same topic as their first one. So, in order to avoid falling into that trap, I decided to just take a vacation in the summer of 2015. For the first time in years I spent my own money on foreign travel, and spent a month in Russia and a month in Turkey--mostly visiting places I had never been.

Why do this? I was hoping to get back to my roots, in some ways. What was it about these countries that I liked in the first place? So I took some good fiction, a notebook, and a backpack and spent two months traveling around, thinking about anything but the subject of my second book.

And then, one day in Istanbul, I was hanging out in a bookstore and I saw a book about Nâzım Hikmet. It wasn't particularly interesting--hundreds of books had been written about Nâzım--but all of a sudden I got an idea. Looking through the book, I noticed that the author hadn't used any archival sources from Russia, and this got me wondering.

Returning to my AirBnB that day, I started searching for information about the more professional-looking biographies of Nâzım. None of them used archival sources--from Russia or anywhere else, for that matter. Instead, as I began to research these books more thoroughly, I began to realize that they all more or less repeated the same old stories, even in cases when they strained credulity.

More research quickly showed me that there were three archives in Moscow that would be beneficial to me in writing a book on Nâzım. Thanks to a fellowship that I received from the Fulbright foundation, I was given access to these archives over the course of an academic year spent in Moscow in 2016-2017. Further research in Istanbul, Amsterdam, Washington D.C. and a return trip to Moscow in 2019 paved the way for my book on Nâzım to be published in 2023.

All in all, the book is quite different from others on Nâzım Hikmet. For one thing, it's not just about Nâzım. Rather, I situate him in a certain context by also looking at others from his generation--Turkish communists who are, for the most part, much more obscure, people who did not go on to become internationally famous poets.

Ultimately, the book is about the transition from a late imperial era of relatively open borders to a post-imperial time that was markedly different. It's not just the story of one man, but rather that of a generation of women and men--"border-crossers," as I call them, people whose lives had been changed in all sorts of ways by their international experiences in the 1920s, only to find the doors closing behind them in the 1930s.

Turks Across Empires

Turks Across Empires (Oxford University Press, 2014) grew out of my doctoral dissertation in the Department of History at Brown University in 2007. However, the differences between the dissertation and the book (which was published seven years later) are substantial. The biggest difference is that, in the book, I make explicit the connections between the pan-Turkists and the communities they lived in, whereas in the dissertation much of this is only hinted at.

In the years following the completion of my PhD, I struggled a bit to figure out what I would eventually do with the dissertation. The dissertation had, in fact, originally been conceptualized as a very conservative intellectual history. I planned to write (yet another) book about the ideas and arguments of Yusuf Akçura, Ahmet Ağaoğlu, and Ismail Gasprinskii through the context of their published writings. My big contribution, as I saw it, was that I would include one (!) chapter in which I discussed the Russia based writings of Akçura and Ağaoğlu.

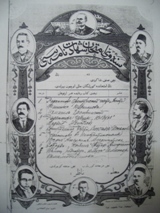

Yusuf Akçura

This direction changed drastically for a couple of different reasons. First, my advisor, Engin Akarli, would never have allowed me to do something so boring and timid. Second, I received a number of important grants and fellowships to do research in Russia, which ended up allowing me to focus much more on Russia than I had originally intended.

Little did I know, topics related to Muslims were becoming increasingly fashionable in the field of Russian history. The only problem, however, was that the great majority of Russianists working on issues related to Muslims have little to no training in the study of Muslim communities or their languages, leading to very state-centric narratives of works which endeavor to examine Muslim-state interactions. So, when someone who had actually had experience researching Muslim communities and their languages began applying for grants to study Russian Muslims, the money began to flow in.

The upshot of all of this was that I ended up spending a long time research in the archives of the former Soviet Union, including stays in St. Petersburg, Moscow, Kazan, Ufa, Simferopol, Baku, and, a little after I finished my PhD, Tbilisi. While I also spent about a year of graduate school researching in the Ottoman archives in Istanbul, what really ended up setting me apart was that I was able to examine Russian-Ottoman relations and Muslim-state interactions within Russia from the perspective of multiple sides. Rather than base my analysis mainly upon Russian-language sources, or Turkic ones, I could use both.

The Writing Process

After completing my PhD, I was pulled in a number of different directions. A lot of this had to do with the fact that I was on the job market for two years after graduation. During this time (2007-2009) I spent one year in New York City working as a post-doctoral fellow at the Harriman Institute at Columbia University, while in the second year I had research fellowships which took me to Turkey, Russia, and Georgia for a total of about 13 monhts. During this time I was mainly interested in publishing journal articles, which I thought would be more helpful with respect to landing a job.

Once I began teaching at Montana State University in the fall of 2009, I began to work on the book manuscript in earnest. In retrospect, I tried to be too cute. Namely, I thought that I could break my dissertation up into three different monographs. One would be about Muslims traveling back and forth between Russia and the Ottoman Empire. A second would be a traditional intellectual history of the pan-Turkists, while a third would focus on the ulema in late imperial Russia.

After a while, however, I realized that these three topics were deeply intersected in my mind, and that it would be destructive for me to try to pull them apart. After thinking about things more closely, I realized that what connected all of the chapters in my dissertation--even those which did not discuss the pan-Turkists at all--were, indeed, the pan-Turkists. What I needed to do, I decided, was make this explicit in a manner that I had not done in the dissertation. The result was Turks Across Empires.

Turks Across Empires

Rather than produce three different books which would, I think, have ended up being rather repetitive with regard to the themes that I wanted to discuss, I wrote a book about the pan-Turkists in a manner that embedded them within their times. I didn't want to write something that would look like all of the other intellectual histories that are already devoted to these people. Instead, I decided to focus upon the lives and careers of the three people at the heart of the book--Yusuf Akçura, Ahmet Ağaoğlu, and Ismail Gasprinskii--as well as of others who traveled in their worlds.

Ahmet Ağaoğlu

This research took me to the places where these figures themselves had lived and worked, including research stays in Istanbul, Baku, the Crimea, and multiple sites in Russia. For this reason as well as for others, I found myself feeling much more connected to the pan-Turkists than I would have if I had focused simply upon their ideas and arguments. Having lived in places like Paris, Montreal, and Istanbul prior to graduate school, and then spending years of my life researching in the archives and libraries of Eurasia, I had developed an understanding of what it means to feel "out of place," as Edward Said puts it in his memoirs. I felt that I identified with these people, and had insights that I could share with respect to what it means to live in-between multiple places simultaneously.

Ismail Gasprinskii

In the scholarship relating to the pan-Turkists--which tends to treat them as nationalist heroes--there is very little accommodation for this type of perspective. But if we look at the pan-Turkists in this way, suddenly they start to have a lot in common with much less well-known Muslims of the late imperial era. Whereas the traditional historiography of these figures treats them as generally austere, even remote, figures who are compared only to other nationalist writers of the era, Turks Across Empires shows how these individuals reflected far broader developments taking place in the time and places in which they lived. By looking at the lives and careers of these individuals, and showing how they fit into those of much larger populations of late imperial Muslims, my goal was to show how their arguments and ideas actually were important. Unlike previous books, which discuss these individuals in a vacuum, my objective was to show how much a part of the bigger story of the late imperial era they actually were.

Some of the best advice that I received during the course of writing the book was to tell a story--one with "a beginning, a middle, and an end," as it was suggested to me. Looking back on things, even a rather simple-sounding formulation like this ended up being extremely helpful. Without question, making the book revolve around just one relatively bloodless topic--"mobility," "citizenship," "Muslim politics," "Muslim administration," "jadidism," "identity,"--would have been more in keeping with the traditions of academic publishing, especially when it's a former dissertation.

But I wanted to write about people, and the pan-Turkists were people whose lives got me interested in a variety of topics because the pan-Turkists were somehow connected to them. So, I didn't just stop with looking at the "mobility" or "citizenship" (or "politics" or "administration" or "identity") in the lives of the pan-Turkists, but rather found myself digging into the archives, the letters, the rare books, and elsewhere to see what else was going on with respect to these issues. And this is what led me into all of the rather wide-ranging set of topics--taking place in various parts of the Ottoman Empire, Russia, and elsewhere--that are discussed in the book.

The approach that I took grew, I think, out of the amount of time I spent in the archives. When I first started doing archival research in Russia in the summer of 2002, it was quite a terrifying experience. I meekly went up to the director of the catalogue room at the St. Petersburg archive RGIA, and haltingly asked in a trembling voice where I could find "documents on pan-Turkism." I looked absolutely ridiculous and felt fully unqualified to be anywhere near a state archive.

RGIA was a bit intimidating back in those days

The second half of the summer went better, fortunately, because instead of working in RGIA (which was on the verge of closing for a few years and therefore was unbearably crowded that summer) I spent July in Kazan. Here, the reading room had plenty of space and the reading room staff was really wonderful. But even though the actual conditions were a lot easier and I was slowly gaining some confidence, I still couldn't find much on "pan-Turkism." As a topic, it didn't make sense, and it helped me learn the importance of listening to the archives. This is true for any source, of course, but I had to re-learn to restrain myself from imposing my categories of thought onto the materials I was reading.

So, I listened, and in Kazan I found little on pan-Turkism but a lot on administration and on the daily lives of jadids (Muslim cultural reformers). Listening is important. I've seen scholars who employ local researchers to find a bunch of stuff for them, then the scholar will come in from abroad and look through these pre-selected materials to use in their research. But it shows, frankly, in the final product, because these works end up discussing their findings in an empty context. They have no idea that the fourteen documents that their hired researcher found for them on topic x are mitigated by the five-hundred documents in the same archive that tell the opposite story. Frankly, most of these archives are so big that you can find evidence supporting virtually any argument. What you need is the perspective--by actually spending some time in these places, rather than just parachuting in--to gain better understanding of where your findings fit in with the story more generally.

Listening to the archives also meant that I ended up spending less time on the arguments and debates of jadids that can easily be found in the jadid newspapers (and about which there are already numerous books), and instead do something like look into the individual lives of jadids living on the cultural front lines. And what I did for jadids I also tried to do for Muslim migrants, tsarist and Ottoman officials, and other characters that appear in the book. One might wonder what all of the things I talk about actually have to do with "pan-Turkism," but the organization of the book felt like a very organic one to me. What linked all of the chapters from my dissertation together was the pan-Turkists, so why not just come out and say it?

Why was I reluctant to embrace the pan-Turkists? I guess because so much of what had been written on these people seemed so...dry. And every time I told someone at the MESA conference that I was interested in the pan-Turkists, they made a face like they'd just inhaled a very smelly odor. The only way, it seemed, that other people could imagine someone writing about the pan-Turkists would be to do it in the crusty old way that people have been doing for decades--poring over the arguments and ideas of writers without ever addressing their place in the wider world of the time. Frankly, there are a number of intellectual historians who do put some blood into their work, but it's also a subfield (at least in the regions in which I work) that's had a pretty dry historiography overall.

It was the sources that helped me change the story I might have otherwise been forced to write. I was able to spend enough time researching abroad (three of the six years I spent at Brown were abroad) to develop my Arabic-script (and Russian, for that matter) paleography skills. This allowed me to bring archival sources and personal correspondence to discussions that usually have been based on the published writings of the pan-Turkists (newspapers and journals that are available in numerous research libraries in the US). Since I had access to so much more, it seemed appropriate that I try to steer the conversation toward what was new and interesting, as opposed to repeating--for the sake of tradition, presumably--lines of investigation re the pan-Turkists that have already been made dozens of times already.

Sitting in freezing archive and library reading rooms across five countries, I found myself asking a number of questions about the direction of my life more generally, but specifically with regard to pan-Turkists I wondered: What world did these people inhabit? Who listened to them? Why do they matter? By embedding these individuals within the time and places they lived, my goal was to show why their ideas actually can tell us something about the era beyond the obsessions of a small group of scribblers.

Moreover, by talking about pan-Turkists--rather than, say, "pan-Turkism"--and using the story of the pan-Turkists as a means of discussing the late imperial more generally (and here the three themes of the book--revolution, mobility, and the politicization of civilizational identity--come into play), I feel like I was able to say something much bigger and much more important than I would have been able to do otherwise.

Perhaps even more importantly, by building the story around people, rather than a concept that I would then try to shoe-horn these people's stories into, I think I ended up writing something that was a lot more readable, too. I like the fact that, pretty much no matter where you open the book, you'll find people with names doing things. In this respect I think the story moves along a lot faster than is normally the case in academic literature.

Ultimately, I wrote about the pan-Turkists in the way that I did because I was mainly motivated to capture the aspects of their lives that interested me. I wasn't terribly inspired, frankly, by their views on nationalism, but I did admire the ways in which they had repeatedly managed to parlay their international and cross-cultural experiences into successively interesting positions. I liked the importance of mobility in their lives, and was intrigued by the manner in which the experiences of the pan-Turkists paralleled those of many others from the time in a manner that no one had yet explored.

This is the way in which I felt empathy for them, and not only because I had spent much of my life criss-crossing the same borders. Rather, I found myself absorbed by the way in which these individuals managed to find ways to fit in not just despite their travels but rather because of them. They used their past experiences to open doors leading to new ones. In this trait, I thought, there was something for me to learn, and in looking at this issue I saw how even these seemingly remote and elite figures were actually quite deeply grounded within the worlds that made them.

Reviews and interviews re Turks Across Empires

Central Asian SurveyCouncil for European Studies

Central Asiatic JournalAlso see the Ottoman History Podcast and a pan-Turkic chat with one of my MSU students on the History RoundtableAre you a Turk across empires?

You can get the book through Amazon and the OUP website.